In its own words, the FIA Formula E championship was created to “demonstrate the potential of sustainable mobility to help create a better, cleaner world.”

In practical terms this means 100 percent renewable electricity, and tyres that last an entire race and can then be recycled.

Mea Culpa – I am not going to consider the enormous logistical effort and emissions associated with getting the Formula E circus from one city to the next. For now, let’s set that aside and think what makes this business model work.

Back in 2014, when Formula E founder Alejandro Agag approached Toto Wolff, the head of Mercedes-AMG Petronas Motorsport, to gauge his interest in signing Mercedes on to the new series, Toto dismissed the idea, doubting that electric racing was different enough from F1 to attract a big enough fan base. Toto was unconvinced: “I didn’t think it would survive the first three years.” “There is no sport larger than F1 if you consider there are 21 races each year, whereas the Olympics is every four years,” Toto added. “It dwarfs everything out there.”

Alejandro Agag, CEO of Formula E Holdings.

Five years later, Formula E has attracted a wide range of participants, including Mercedes and Porsche, together with teams from other OEM’s including Audi, BMW, DS, Jaguar, Mahindra, NIO, Nissan and Venturi. One financial attraction for OEMs is that Formula E participation requires a fraction of the investment that is needed to become competitive in F1.

The Audience

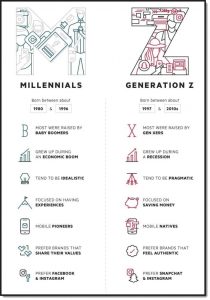

Now in its sixth season, the Formula E championship has succeeded in mobilizing a new audience and created a distinctive public profile that has rewarded sponsors and backers alike, not least in connecting them with its younger, urban audience. Fully 50% of engagement on the Formula E Facebook page is from people in the 13-17 and 18-24 age groups, according to figures from Formula E. The company says that the 18-24 category is their second-largest “follower group” on the social network, after the 25-34 year-olds. I would be interested to see the absolute numbers because I know very few people under 30 who are active on Facebook!

Formula E’s TV audience is growing at quite a pace – however, this may be due to a focus on doing deals with “free to air” television groups, such as the BBC in the UK, where races are more likely to attract big audiences, this approach precludes deals with pay-TV groups that would generate income for Formula E. Like all early-stage companies Formula E is growing its base – the profits will hopefully come later.

Formula E has also developed some novel ways for its fans to interact directly with the races:

Fanboost: Enables supporters to give their favorite driver a five-second power boost. Fans vote for the drivers online, using the Formula E app or via Twitter. The three drivers with the most votes receive a turbo boost of power, which they can use during the second half of the race. Giving the drivers a (possibly unfair) advantage over the rest of the pack, and for traditional motorsport fan, this is unthinkable.

Attack Mode: Drivers can unlock a short power boost by driving off the racing line. Organizers decide the location of the trigger point an hour before the race starts, which means teams don’t have long to adjust their race strategy. The lack of pitstops for the new Gen 2 cars in Formula E probably necessitated the introduction of his new variable to create an element of strategy.

Victory in Formula E races is not just who finishes first — you have to go as fast as you can on as little energy as possible. Michael Carcamo, global motorsports director at Nissan, says that “the whole point” is to “extract the maximum energy from the powertrain while using minimum energy.” The sport is more than a race series, Michael says, as it embodies a serious social purpose by showing how technology can tackle global problems such as climate change and air pollution.

The Formula E Gen 2 cars are more potent than Gen 1, with a top speed of around 280kph (174mph), and improved battery life. Before its introduction, drivers had to switch vehicles mid-race, which simulated an F1 pitstop but also served as an uncomfortable reminder of the limitations of electric technology. The swapping of cars rather than just battery packs also confirmed that battery swapping isn’t the solution some imagine it to be.

Sidebar: The forty Gen1 cars which were owned by Formula E and leased to the race teams were sold off to collectors and museums with prices ranging from $200k to $300k – depending on their race history.

Formula E racing takes place in city-center locations. This approach has enabled the series to operate in a manner similar to attending a football match. Fans can get to events on foot or by public transport – there is no public parking at events. The absence of emissions and the reduction in noise attracts families with young children. Interestingly, the last two races of season 6 will take place in London’s Docklands, where part of the circuit will run through the Excel arena, another unique development. Cities now pay fees to host a round of the Formula E championship.

The Sponsors

Formula E appears to be working for the sponsors, recording TV audiences of up to 411m people in 2019, a 24 per cent rise from a year before, albeit significantly short of the1.6 billion cumulative broadcasting audience for Formula 1 over the same period. However, Formula E backers are patient.

“e-mobility is at the core of what we are doing. Studies tell us that the younger demographic wants to be connected with brands that convey an authentic purpose and mission.”

Nicolas Ziegler, head of markets, brand and events, ABB.

“Formula E is not just a car race; it is a race with a purpose: to create enthusiasm for electric mobility, to promote research and development.”

Marco Parroni, head of global sponsorship at wealth manager Julius Baer, an official worldwide partner to the championship.

“The appeal, first and foremost, is the association with innovation, teamwork, and sustainability.” “Those are the pillars that we want our brand associated with.”

Gary Grose, Argo Group’s global marketing and communications leader.

“Porsche’s all-electric consumer model, the Taycan, is on sale and by 2025 we want 50 percent of new vehicle sales to be electric. We are looking for a competitive environment to prove what we are capable of developing,”

Malte Huneke, project leader at Porsche.

The realization that Formula E could help market the new generation of electric vehicles is why Mercedes joined the championship. Mercedes is planning to roll out ten all-electric models by 2022, and it sees Formula E as a platform to showcase its leadership in this emerging technology, according to Toto Wolff.

“The early adopters of E vehicles were switching to be conscious of the environment, but if you want to have a big movement of people adopting these cars, you need to address the heart.” According to Britta Seeger of Mercedes-Benz Cars.

Britta Seeger, responsible for Mercedes-Benz Cars Marketing & Sales.

Formula E’s focus on marketing has drawn criticism. Red Bull consultant Helmut Marko once dismissed the series as “a marketing excuse from the automotive industry to distract from the diesel scandal.” He also scoffed that Red Bull would not join as they are “racing purists.”

Michael Perschke, chief executive of Automobili Pininfarina, would disagree. “I think Formula E will be for the next generation what F1 was for the last generation. Why? It’s an interactive series. It is not a format limited to the old Bernie Ecclestone system where if you paid hundreds of millions, you got in. . . It’s Racing 2.0.”

Financial Sustainability of Formula E

Alejandro Agag, stated the company’s revenues were more than €200m ($223m) in the year to July 31 2019, a period that covers the group’s fifth racing season. He said earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization for the year were positive for the first time, at about €1m ($1.12m). Mr Agag added this had been achieved without cutting the group’s marketing budget of about €30m ($33.5m).

“Reaching break-even is a historic moment for us,” said Mr Agag. “For a business that almost didn’t make it after three races, now after 60 races we reach breakeven — and with strong revenue growth — and that is going to continue.”

He declined to provide a full financial breakdown of Formula E’s results, which are yet to be lodged with Companies House in London. But he said sponsorship, which accounts for about half of total revenues, had grown 25 per cent in 2019. That was on the back of four new corporate endorsements, with German electricals group Bosch, Dutch beer maker Heineken, French champagne brand Moët & Chandon and Saudi Arabian Airlines.

Sponsors “keep coming, and they keep renewing for longer and longer”, Mr Agag said. “What they want, and what they perceive, is that Formula E . . . is definitely a bet for the future.”

Formula E is based out of London, and its biggest shareholder is Virgin Media-owner Liberty Global, which has a 23.9% stake. Its other shareholders include Swiss bank Julius Baer and New-Wave, the ultimate parent of Weibo, China’s equivalent of Twitter.

According to Formula E chairman Alejandro Agag, the sponsorship market has changed. Corporate groups once paid for brand “exposure,” but online advertising platforms such as Google and Facebook have made it possible to target millions of consumers like never before. As a result, says Mr. Agag, partners now care more about the narrative they can spin through their association with a specific sport.

“Sponsors care about what stories they can tell of why they are partners with you,” says Mr. Agag. “We are in line with the movement that is helping preserve the environment, helping to fight climate change, helping to fight city pollution. Those are the kinds of stories that sponsors are attracted to.”

Chase Carey, CEO and chairman of F1, told the Financial Times that he saw Formula E as a “business to business proposition, as opposed to a sport.” In other words, the Formula E championship is a marketing ploy for companies that want to be associated with environmentalism, but not a particularly exciting event that audiences want to watch.

Less Carrot and More Stick in Europe

Europe’s carmakers are gearing up to make 2020 the year of the electric car with a wave of new models launching as the world’s biggest manufacturers scramble to lower the carbon dioxide emissions of their products. Some incentives remain to adopt electric cars, but what we are now seeing in the EU is the introduction of regulations and fines.

New European Union rules came into force on 1 January that heavily penalize carmakers if average carbon dioxide emissions from the cars they sell rise above 95g per kilometer. If carmakers exceed that limit, they will have to pay a fine of €95 ($106) for every gram over the target, multiplied by the total number of cars sold.

To illustrate the scale of this change, the excess emissions bill based on 2018 sales figures would have been a staggering £28.6bn ($35bn), according to an analysis by the automotive consultancy Jato Dynamics. “It is challenging for carmakers to change manufacturing infrastructure in such a short period,” says Jato analyst Felipe Muñoz.

Carmakers have successfully lobbied for a rule that means cars emitting less than 50g of carbon dioxide per kilometer are eligible for so-called “super-credits,” a controversial policy which means that every electric vehicle sold counts as two cars. That makes it easier for carmakers to meet their targets, even if average emissions from their cars are higher than the rules stipulate.

Which brings us to Tesla. The company is enjoying record sales up 50% in 2019 and a record stock market valuation, becoming the highest valued US automaker of all time, closing at $81.39 billion in early January 2020. With demand currently exceeding supply there is little incentive for Tesla to burn marketing dollars on Formula E. Furthermore in its current format Formula E offers no opportunity for Tesla to showcase its proprietary battery and motor technology.

The stars are aligning.

European car manufacturers are now highly motivated to build and sell electric cars to avoid substantial financial penalties. Formula E offers an exciting platform for car manufacturers to be associated with sustainability and the cutting edge of electric vehicle technology. At the same time, they are tapping into a younger, greener, more affluent audience – and hoping to persuade them to buy electric cars.

Along the way we might even get to enjoy some exciting racing based on sustainable technology. When diehard petrol head Jeremy Clarkson said he would rather watch Formula E than Formula 1, it perhaps marked a coming of age for electric racing.

Adrian G Stewart